Here at the Martin Center, we often criticize university research. Rightly so.

We have noted that academic journals are too expensive. We’ve argued that the publishing process itself is incoherent and slow. And that the peer review process fails to adequately vet new research. We’ve shown that the funding process for scientific research often leads to perverse incentives. We’ve also commented on the well-known reproducibility crisis in the social sciences.

We have also pointed out that research, especially in the humanities and social sciences, is often trendy, repetitive, or irrelevant.

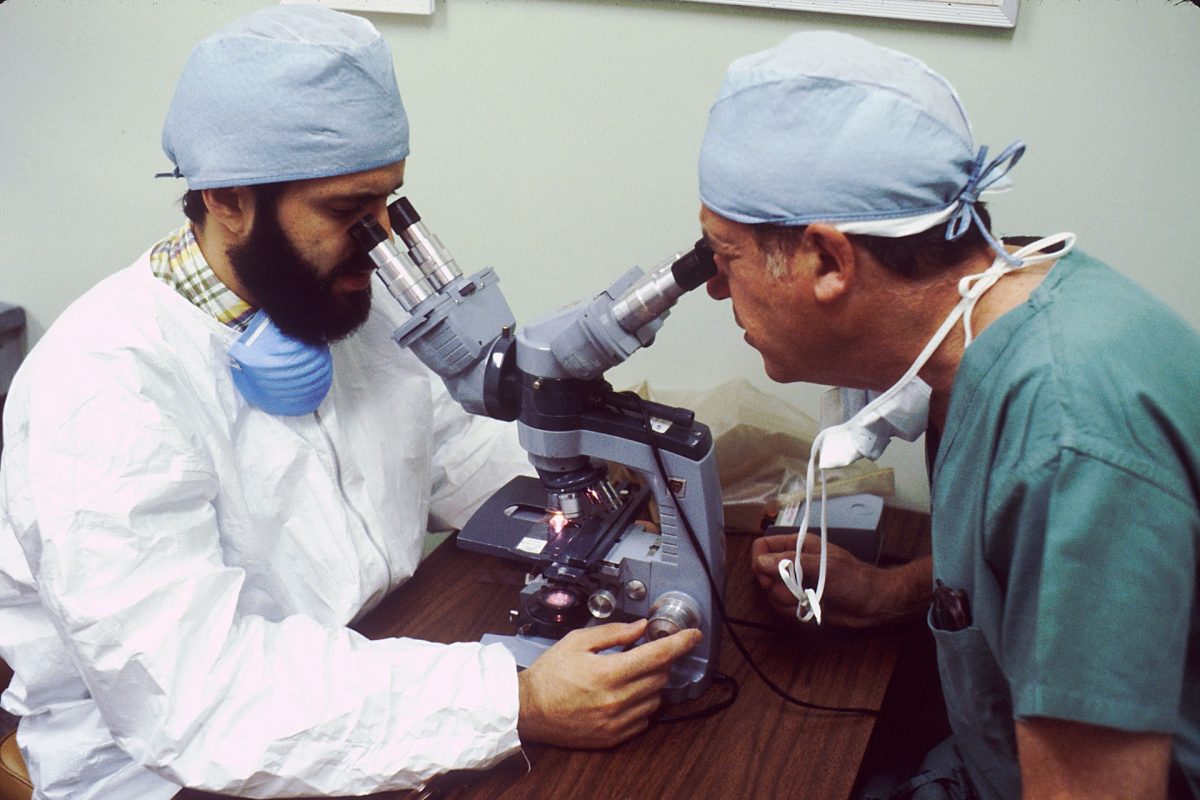

But in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, university researchers—working side-by-side with entrepreneurs and philanthropists—have shown that there can be immense value in studying important problems and harnessing expertise in the name of public service.

Here are a few examples of university researchers investigating solutions for the COVID-19 pandemic and the health care crisis it has created in cities around the world:

- On March 4, Bloomberg Businessweek profiled a “University of North Carolina scientist who has been chasing viruses for decades [and] may hold the key to a cure.” Ralph Baric is an expert on coronaviruses who works at the UNC-Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health. (Baric is also cited in this article in Nature Medicine from 2015 entitled, “A SARS-like cluster of circulating bat coronaviruses shows potential for human emergence.”)

- On March 19, a Johns Hopkins’ publication, Global Health NOW, highlighted research by Arturo Casadevall, chair of the Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. He and his coauthor, Liise-anne Pirofski of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, are looking into ways to use “plasma (serum) from the blood of survivors until a vaccine and antiviral medications are available.”

- On March 26, UF Health shared an invention by Bruce Spiess, MD, a professor of anesthesiology at the University of Florida College of Medicine. Spiess created a simple respirator mask out of materials that are already widely available in hospitals and medical facilities.

- Also on March 26, Extremetech reported that an “MIT team has developed an open-source ventilator called the MIT E-Vent that could get regulatory approval soon.” The ventilator is manual but could save lives in an emergency.

- On March 27, Rice University unveiled its own “automated bag valve mask ventilation unit that can be built for less than $300 worth of parts.” The researchers will make the plans for the ventilator freely available online. The ventilator was created in conjunction with Canadian global health design firm Metric Technologies.

- Also on March 27, the Triangle Business Journal touted an innovation pioneered at Duke Health to sterilize and reuse medical masks. Duke’s director of Occupational and Environmental Safety Matthew Stiegel says they have been using the technique for years in their biocontainment laboratory.

- On April 1, the Economic Times reported on an as-yet-unpublished report by Gonzalo Otazu of the New York Institute of Technology. The report uses evidence from the U.S. and Italy to hypothesize that tuberculosis vaccines could protect against COVID-19.

There are many more examples—too many to list them all here.

Universities are also helping us understand the scope and trajectory of the crisis. By now, many of us are very familiar with Johns Hopkins’ heatmap of COVID-19 cases, created by the university’s Center for Systems Science and Engineering.

And the models that have guided world leaders as they made decisions about their virus response were created by university researchers. First, the Imperial College of London’s dire coronavirus model prodded reluctant leaders into taking action. (It was later revised to have less-dramatic projections.) A model from scholars at Oxford University suggested that many people in the UK already had coronavirus but showed no symptoms. And now, many states and countries are using a model from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington to anticipate medical needs. It, too, was revised as more data became available.

Also helpful is the US Health Weather Map by Kinsa Insights, which was created in partnership with Benjamin Dalziel, an assistant professor in the department of integrative biology at Oregon State University. The map is a “visualization of seasonal illness linked to fever—specifically influenza-like illness.”

Science is an iterative, collaborative process wherein various researchers publish, critique, and revise their work—slowly moving the field forward.Social science and public policy programs have contributed as well, suggesting economic and policy solutions to the problems caused (or revealed) by the coronavirus pandemic. In this working paper, authors from Duke University’s Margolis Center for Health Policy suggested ways in which the FDA can improve its efficiency. And in another paper, they outline a plan for testing and tracing that could be implemented in the U.S.

It’s still unclear which solutions will work and which models will prove most useful. Some may be wrong. Science is an iterative, collaborative process wherein various researchers publish, critique, and revise their work—slowly moving the field forward. Frequent, specific, constructive criticism—which has been available in abundance during this crisis—contributes to the process. Such is the nature of scientific progress.

Nonetheless, universities have shown throughout the COVID-19 pandemic that when they focus on their core mission—preservation, discovery, and transmission of knowledge—they can provide immense value to society.

When this crisis is over, university leaders will surely face many difficult decisions. I hope they remember this lesson from COVID-19: a university’s true value lies at its academic core. It is not a sports franchise, a real estate developer, or a social club. At its best, a university is a wellspring of ideas, an edifice of knowledge.

Jenna A. Robinson is president of the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal.