Students in the United States have unprecedented options for postsecondary education: from brick-and-mortar liberal arts institutions and research-intensive doctoral universities to dual-enrollment high schools and online-only degree programs. Entrepreneurs are innovating continually to improve America’s higher education options.

But a new report attempts to throw cold water on the higher education landscape. Entitled, “Disconnected from Higher Education: How Geography and Internet Speed Limit Access to Higher Education,” the report claims that 3 million Americans live in “higher education deserts.” The report is co-authored by Victoria Rosenboom and Kristin Blagg, researchers in the Urban Institute’s Education Policy Program.

When taken at face value, the report’s conclusion is cause for celebration: almost 99 percent of American adults have easy access to adequate learning options. This is a remarkable achievement. The report then focuses on the remaining 1 percent of American adults who have access to neither physical nor online education.

Setting aside whether 1 percent represents a significant threshold of Americans lacking higher education opportunities, there are problems in the report’s data and analysis that put even this tenuous conclusion in doubt. It may be that higher education “deserts” are even smaller than reported.

The report’s first misstep is its definition of a physical higher education desert, which includes any place where the only available broad-access brick-and-mortar option is a community college. The American Council on Education used the same definition in its 2016 report, “Education Deserts: The Continued Significance of ‘Place’ in the Twenty-First Century.”

ACE’s explanation is useful in understanding the methodology of both reports:

Having only one community college and no other public broad-access college or university nearby means the student only really has one public option from which to choose. If there are two community colleges, or if there is a community college and a broad-access public university, then this community would not qualify as an education desert under this definition since the student has at least one public alternative. Under this definition, a community could still be classified as an education desert even if private institutions operate nearby.

Precedent aside, this defies any common sense understanding of the idea of a “desert.” A higher education “desert” ought to be strictly defined as a place where residents have no access to higher education—not a place with multiple options that fall outside strict, predetermined parameters.

The definition of “online education desert” used in the report is also misleading. The report’s authors use the FCC’s definition of “broadband internet” (25 megabits per second) as the metric—an unnecessarily high bar. Students do not need such high capacity to take an online course. (For comparison, Netflix recommends its users have internet speeds of 5 megabits per second to stream “HD Quality” content.)

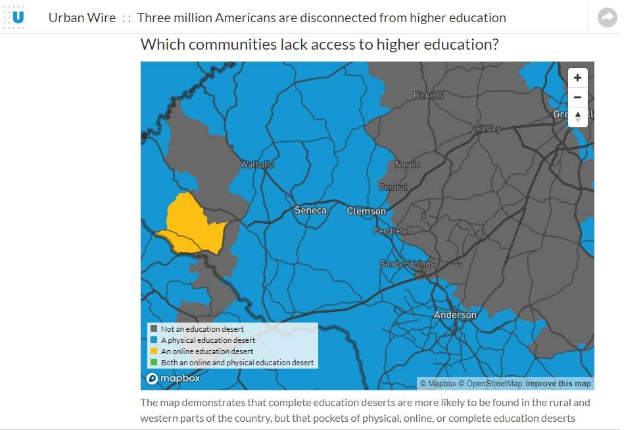

Using more reasonable standards yields a different picture. Very few Americans have no colleges or universities within driving distance and internet speeds under 5 megabits per second, but the map data in the report obscures this reality. For example, the upstate South Carolina region appears empty on the report’s graphic data, a physical higher education desert.

This may surprise readers familiar with the area given that Clemson University, Anderson University, Tri-County Technical Institute, and several other institutions all offer higher education to local residents. For example, Anderson University is dismissed from the report because it is a private school, though it actually offers classes to local high school seniors. And Clemson University, which the authors consider “inaccessible” for having high academic standards, offers a “Bridge to Clemson” program in conjunction with Tri-County Technical College, a local community college. The program allows students to be admitted to Clemson with 30 transferable credit hours. These programs are excellent examples of extending educational opportunities to local students. It is hard to see how any close observer of upstate South Carolina could consider it an education desert.

There are equally puzzling examples in North Carolina, too. The town of Rolesville, for example, is on the edge of a “physical education desert” despite being located in Wake County, which hosts 12 colleges and universities. The town itself is a 10-minute drive from the northern campus of Wake Technical Community College, one of the largest community colleges in the state. Elizabeth City is also listed as a “physical education desert,” although Elizabeth City State University and the College of The Albemarle are both located within its city limits. College of The Albemarle serves students from Camden, Chowan, Currituck, Dare, Gates, Pasquotank, and Perquimans counties.

By contriving a definition that suits a pre-disposed conclusion, the report misses a broader element in the discussion of higher education. If anything, there is an over-supply of colleges and universities in the United States. Many schools, even those in heavily populated areas with many eligible students, face financial difficulties. And in the Northeast, where the population is declining, students are spoiled by choice as colleges and universities vie to give them the best offers of tuition discounts and special programs. Enrollments have continued to fall for the past six years.

Lastly, the more fundamental scarcity facing students today is having access to appropriate job skills, not institutes of higher education per se. A survey to know where genuine opportunities to gain desirable skill sets are lacking would prove more useful in reaching those left behind. Fortunately, technical education is abundant. Vocational colleges offer the appropriate means for a large portion of the labor force to get ahead in today’s economy.

Traditional research-supported schools, on the other hand, offer plenty of signal value to the marketplace, but offer only questionable skill sets at best, as Bryan Caplan explained in his recent book. He argues,

When we look at countries around the world, a year of education appears to raise an individual’s income by 8 to 11 percent. By contrast, increasing education across a country’s population by an average of one year per person raises the national income by only 1 to 3 percent. In other words, education enriches individuals much more than it enriches nations.

Privileging public universities places the “need to signal” over the “need for skills” in a way that ultimately makes educational opportunities less attractive. Increasing the presence of bricks-and-mortar public universities would only dilute this signal value further, thus creating the need for more educational opportunities to better signal ability. Surely it is not simply being in the august hallways of public university buildings that benefit students. It is by gaining skills that provide the potential for personal growth throughout their lifetime.