Editor’s Note: This article is a response to a December Martin Center article on Christian colleges and student debt.

In his recent article, “Are Christian Colleges Worth the Debt Burden?” Douglas Oliver argues that Christian colleges have a responsibility to reduce the tuition they charge their students to avoid excessive borrowing. He invokes a version of the Bennett Hypothesis, stating that “the business model for most Christian colleges is based on high levels of student debt” and that “Christian colleges need to ‘walk the walk’ by discouraging their students from taking out large life-altering levels of debt.”

Oliver states that, as a group, Christian colleges have 1) lower-than-average default rates, 2) lower graduation rates, and 3) average long-term earnings for alumni.

While I share Oliver’s concern for students who drop out of college with onerous debt levels, that is not a phenomenon unique to Christian colleges.

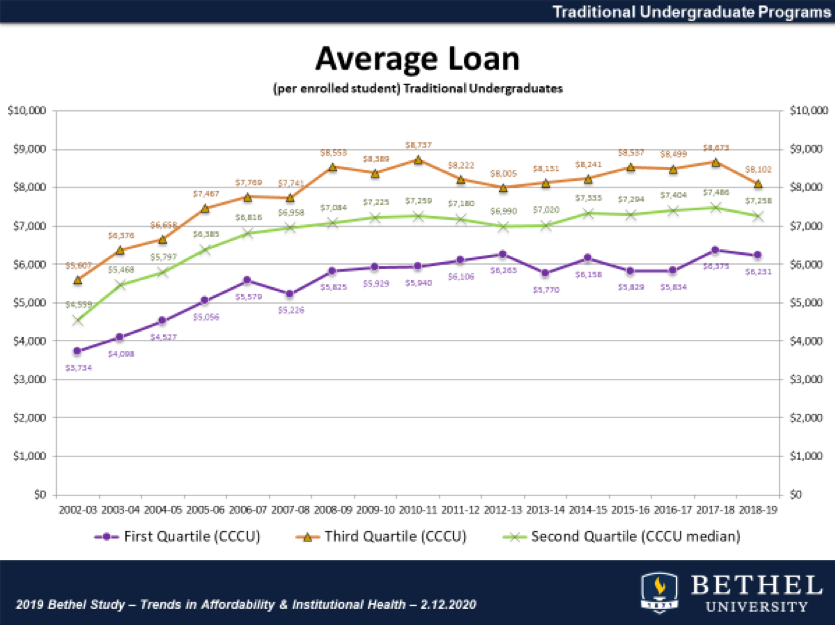

I believe that students fare better at Christian colleges, both the well-prepared and those with lesser preparation or ability. I also believe that, rather than being motivated to raise tuition due to the availability of student loans, market forces push Christian colleges (and all private colleges) to control the net costs incurred by students and families. That effort has led to relatively flat loan levels over the past decade.

The default-rate advantage for Christian colleges (3.5 percentage points lower than non-Christian colleges) is significant. The student loan repayment rate at Council for Christian Colleges & Universities (CCCU) institutions is 73.8 percent vs. the national average of 64.5 percent. Apart from one outlier, all 129 U.S.-based CCCU schools have default rates well under 20 percent, and 87 percent are under the national average of 10.1 percent.

Even though the national four-year private college group includes Ivy League schools such as Harvard, over half (54 percent) of CCCU schools have default rates below the national average for private, non-profit four-year colleges. I attribute that result both to the character of our students and the counsel they receive from their Christian college financial aid personnel.

A discussion of graduation rates requires nuance. Graduation rates are a function of the size and selectivity of a school as well as the academic preparation of the students. The latest data (the cohort entering in fall 2011) shows that the national average 6-year grad rate is 59 percent for CCCU schools and 64 percent for non-CCCU four-year, non-profit private schools. But that latter metric includes Harvard and 68 other schools with enrollments of over 10,000 students with a weighted average six-year grad rate of nearly 75 percent. By contrast, only two CCCU schools are so large.

A more meaningful comparison would be to compare schools with small-to-medium-sized enrollments. For schools with enrollments under 5,000 students, the weighted average six-year grad rates are similar—56.9 percent for CCCU schools and 58.6 percent for non-CCCU schools. When looking at the smallest schools (under 1,000 students), the 27 CCCU schools have a weighted average six-year grad rate of 46.5 percent, higher than 43.1 percent for non-CCCU schools.

But why should grad rates be lower at smaller schools? That has to do with the mission of the schools and the diverse populations they serve. Fifty years ago, when I enrolled at Bethel University, a small Christian college, most families sent their children to the school for a grounding in their faith before transferring to a larger school to complete a specialized major not on offer. The six-year grad rate hovered around 40 percent. Since then, the school has grown, added majors, and maintains a grad rate approaching 75 percent.

Our smallest Christian colleges are much like the school I attended a half-century ago. Mostly denominational and operating on modest budgets, they serve a higher share of low-income and first-generation students. Nonetheless, they maintain a higher grad rate than comparable secular private non-profit colleges. Many of their “dropouts” transfer elsewhere and complete their degrees.

Alumni earnings data for colleges have become more available in recent years, and it shows that Christian colleges have similar salary outcomes. For earnings outcomes, Christian colleges do well, especially considering that their comparison group includes elite schools and Christian college graduates gravitate toward lower-earning service professions (12.7 percent of CCCU grads pursue careers in human services vs. 4.2 percent from all four-year institutions).

Oliver states that “Many Christian colleges, given that they rely on tuition revenue, have an incentive to encourage more debt. To change their incentives, Christian colleges need to find a funding model that’s less reliant on tuition revenue or reduce expenses so students can avoid taking on too much debt.”

Yet, rather than encouraging debt, I have found while consulting at Christian colleges and speaking with financial officers that schools do all they can to advise students to avoid excessive debt. Good debt counseling is taught at the Ron Blue Institute for Financial Planning, which was founded at Indiana Wesleyan University and has spread to other campuses. Christian colleges are limited in stopping students from taking debt, however: In most cases, schools that participate in Title IV government aid programs may not refuse to endorse government loan applications for which the student is eligible.

Christian schools are acutely aware of the impact of debt on their students and are taking several steps to control the cost of a Christian college education. Very few have substantial endowments with which to “subsidize” tuition. For Christian donors, I encourage them to consider establishing endowment funds to help needy and deserving students. Without additional funding sources, Christian colleges are scaling back expenses, which has kept the median net cost of a CCCU college between $20,000 and $21,000.

Adjusting for inflation, the median net cost of attending a CCCU college is less today than it was 7 years ago. As a result, annual student borrowing has plateaued, as has the total debt of graduates.

I agree with Oliver that prospective college students should be wise in their college selection process, considering their career goals, academic preparedness, and financial situation. Colleges have a responsibility to provide clear information on the advantages and costs of their school. In the end, though, I maintain that a Christian college is often the best choice for a young person seeking to mature in their faith and make it their own.