Conventional wisdom and public perception hold that college sports provide educational opportunities for thousands of student-athletes who could not afford to attend college without them. The National Collegiate Athletic Association lists “providing opportunities to earn a college degree” as at the heart of its mission and boasts that nearly 500,000 student-athletes participate in college sports each year.

Nonetheless, a vexing question remains unanswered, and usually unasked: who pays for the educational opportunities that benefit many college athletes? This is the question that we attempt to answer in a recently published article in the Journal of SPORT. The answer may surprise many and upset some, but it is all too clear. First, colleges and universities vary significantly in the amount of institutional funds that go to subsidize college athletics, and second, the colleges and universities that provide the highest institutional subsidies to college athletics are far too often schools that serve a student population that faces the greatest academic challenges and financial need.

We examined data from a 2015 article in The Chronicle of Higher Education that provides insight into how more than 200 public Division I colleges and universities financed their athletic programs from 2010 to 2014. Because the majority of athletic programs do not earn enough in revenues to cover their costs, most colleges and universities transfer resources from their broader institutional budgets to their athletic programs. Subsidies from institutional budgets to athletic programs can reach into the tens of millions of dollars, and account for an average of over 53 percent of athletic revenues and a still higher median of over 65 percent of athletic revenues. Even more interesting, however, is a closer look at how these subsidies vary across institutions and impact the students these institutions serve. Here is where our analysis shows why the conventional wisdom and public perception are only partially true.

Our first finding is that the transfer of institutional resources to the athletic budget each year, on a per-student basis, falls dramatically as the number of undergraduates increases. Large flagship state universities are home to athletic departments that in many cases are successful on the field and court— and at the cash register. Teams from these schools often play in bowl games and receive bids to the NCAA basketball tournament. They typically draw heavily at the gate and earn millions more from lucrative television contracts. Athletic departments at six large schools in our sample of 203 earned revenues that exceeded their costs and did not receive any transfer of institutional funds. Even if athletic programs at large schools run a deficit, it tends to be small and is spread over a large population of students, making the subsidy per student trivial.

The story is quite different for small state schools. With fewer bowl and tournament appearances, a smaller, less enthusiastic fan base, and fewer media dollars, the athletic departments at these schools generate far less revenue and fund a larger share of their budget from institutional resources. Given that these schools have fewer students, the yearly subsidy tends to be much larger per student.

Our second finding, when we examine what kind of students attend which schools, illuminates how the conventional wisdom breaks down. We found that students who are less prepared academically and who have fewer financial resources are more likely to attend smaller institutions, where the subsidy to athletics is much larger. To evaluate students’ academic readiness for college, their success while in college, and their financial capacity to pay for college, we used data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education System. We considered two academic criteria and two financial criteria for students at each institution in our sample. Our academic criteria were the average ACT score of the bottom 25th percentile of incoming first-year students and the six-year graduation rate, and our financial criteria were the shares of first-year students receiving Pell grants and student loans.

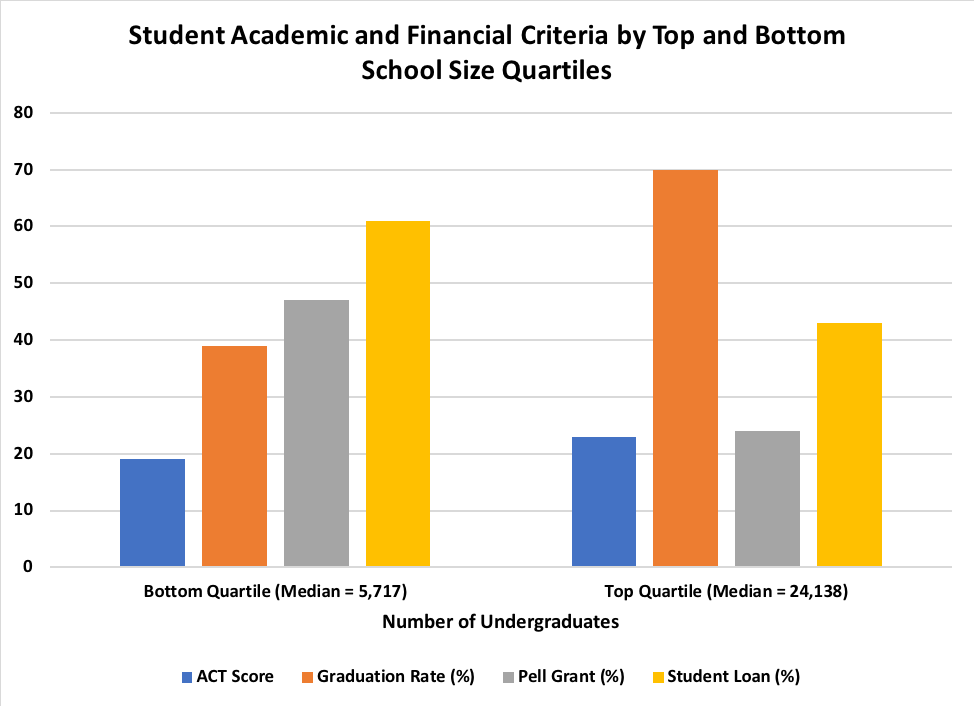

When we contrast the quartile of smallest schools, with a median undergraduate enrollment of 5,717 students, with the quartile of largest schools, with a median undergraduate enrollment of 24,138, the differences are striking, as illustrated in the chart below.

- The median ACT score at the small schools was four points lower (19 vs. 23).

- The median graduation rate at the small school was 31 percentage points lower (39 percent vs. 70 percent).

- The share of students receiving Pell grants at the small schools was 23 percentage points higher (47 percent vs. 24 percent).

- And, the share of students receiving student loans at the small schools was 18 percentage points higher (61 percent vs. 43 percent).

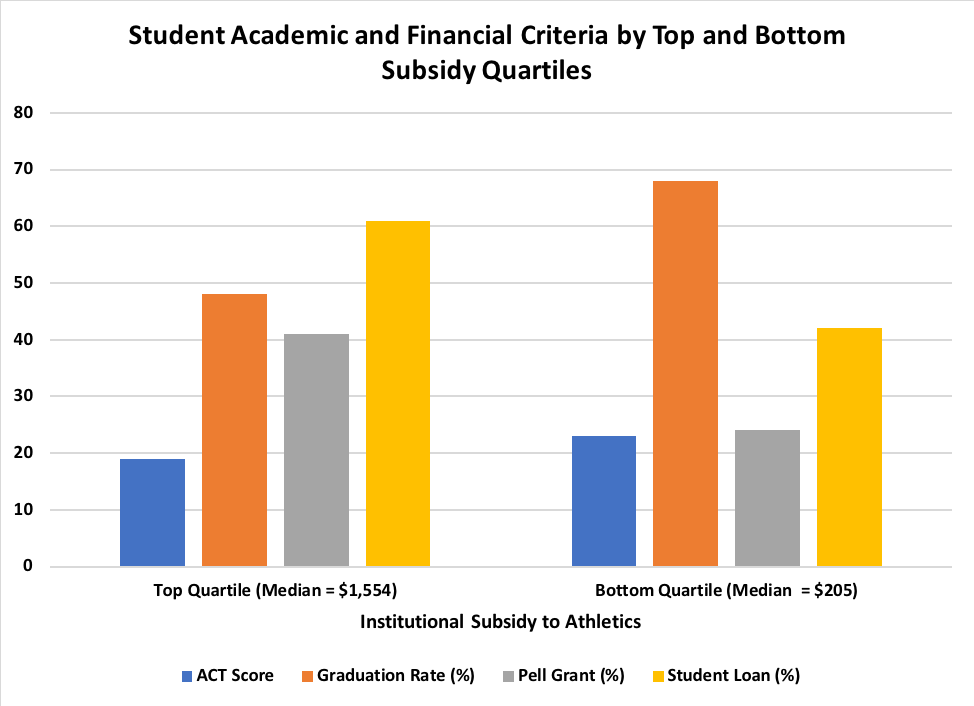

Now, what about the subsidies? Similarly, we divided schools into quartiles, this time based on the annual, per-student transfer of funds to athletics from the institutional budget. For the quartile where the subsidy is highest, institutional funding to athletics is a median of $1,554, but where the subsidy is lowest, it plummets to only $205. The contrast from an examination of students’ academic capabilities and financial resources is striking, as illustrated in the following chart.

- The median ACT score at the high-subsidy schools was four points lower (19 vs. 23).

- The median graduation rate at the high-subsidy schools was 20 percentage points lower (48 percent vs. 68 percent).

- The share of students receiving Pell grants at the high-subsidy schools was 17 percentage points higher (41 percent vs. 24 percent).

- And, the share of students receiving student loans at the high-subsidy schools was 19 percentage points higher (61 percent vs. 42 percent).

We do not contest the common assertion that college sports provide educational opportunities to countless student-athletes who may not have such opportunities without them. We do, however, argue that this assertion—and the endorsement of college sports that accompanies it—loses its luster when confronted with the truth that at small schools, these opportunities are disproportionately paid for by non-athletes. In addition, a greater proportion of students at these schools lack the skills to succeed in the classroom or the dollars to pay the bursar. Resources have alternative uses, and resources devoted to athletics could be channeled to academic support or lower tuition bills, especially today when the high cost of a college education and heavy student debt loads are being questioned.

College athletics surely gives to some, but it assuredly takes from others as well. Parents, students, and the public are typically unaware that the educational opportunities heralded by the NCAA and athletic supporters come at a cost—a cost often paid by non-athletes, many of whom face significant academic challenges and have substantial financial need. The perception about the link between college sports and educational opportunity may be true—but only halfway.