Step 1: Spend more on universities.

Step 2: Get more graduates.

Step 3: Statewide prosperity!

Sounds pretty simple and straightforward, right? (At least for fans of the very NSFW program South Park.) States with more educated residents tend to have higher incomes. So it seems only natural that investing more taxpayer dollars in higher education should lead to stronger economic growth via more graduates. Indeed, it’s a simple proposal often made to state lawmakers by university administrators and their assorted allies.

Spending more doesn’t lead to states having more educated populations.If only it were so simple.

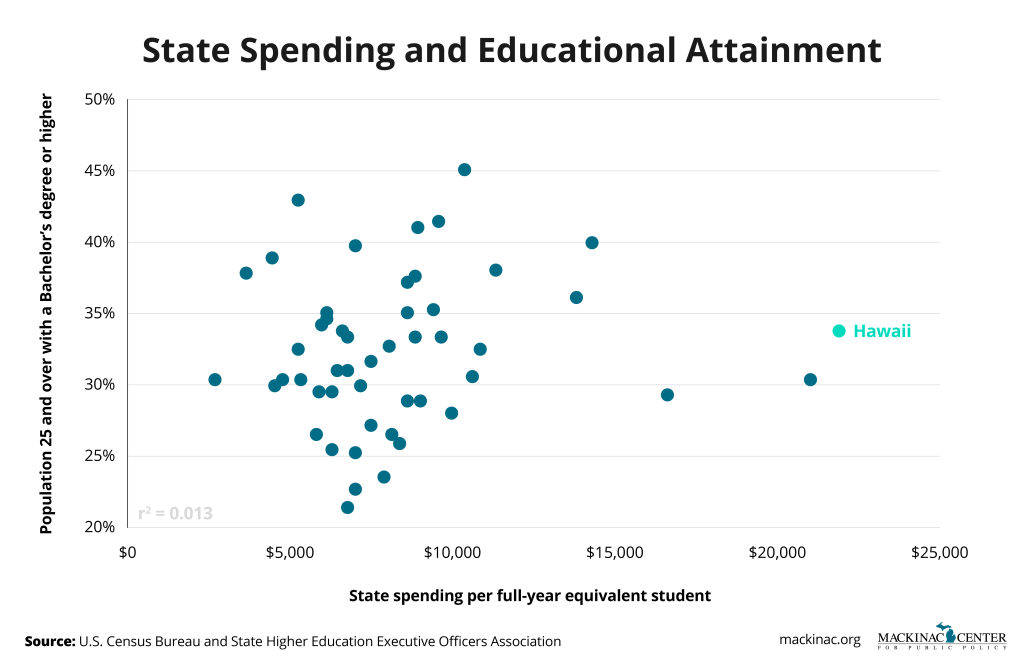

Below is a chart showing taxpayer spending per student, by state, as well as each state’s educational attainment. Each dot is a state. So, for instance, the dot at the far right is Hawaii, which spends a high amount on higher education—$21,960 per full-time equivalent student—but is around the middle of the pack for the population of adults with a college degree.

If the theory worked, then states should be clustered around a line leading from the bottom left to the top right. Such a connection doesn’t exist.

Spending more doesn’t lead to states having more educated populations.

Of course, it shouldn’t be surprising that taxpayer funding doesn’t result in an educated populace. Lawmakers don’t attach a lot of strings to their tax dollars, nor do they do much to reward success.

If anything, schools use taxpayer funding to supplement what they charge students in tuition. (As the Martin Center recently reported, federal dollars often cause tuition to rise.) The thinking is that supplementing tuition might encourage more people to attend, and perhaps even to graduate.

State lawmakers should be much more judicious about how they subsidize higher education.However, if students cared about the costs of higher education, there would be a lot more price competition between colleges. Instead, schools tend to compete over other things, like amenities, facilities, and social-justice do-goodery. Sometimes, students and parents do indeed get concerned about tuition costs, and admissions officers are pretty good at alleviating those worries. Loans are available if the out-of-pocket cost of attendance is too high. And the college degree is the perceived ticket to the middle class, so the expense will more than pay for itself.

Despite the lack of connection between state funding and outcomes, the United States as a whole has become more credentialed. According to the Census Bureau, the percentage of adults with a bachelor’s degree increased from 27 percent in 2006 to 35 percent in 2021. But this is unlikely to have been caused by states deciding to spend more taxpayer dollars on universities. The phenomenon has much more to do with credentialing as a de facto employment standard, to name just one probable cause.

State lawmakers should be much more judicious about how they subsidize higher education. They ought to ensure that taxpayers get something in return for their spending. Finally, they ought not to expect, without evidence, that additional dollars will lead to a richer state population. It doesn’t.

James M. Hohman is the director of fiscal policy at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy.