In the fall of 2018, the trustees of Washington and Lee University voted to paper over parts of the university’s history.

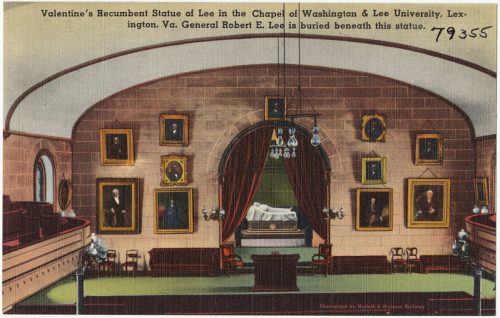

On the recommendations of Washington and Lee’s “Commission on Institutional History and Community,” the board voted to close off the Recumbent Statue of Robert E. Lee in the university chapel that bears his name and to remove the name of John Robinson from an important campus building.

A group of alumni were concerned by those decisions and started to dig deeper. They discovered that those weren’t the only attempts to de-emphasize their school’s history. Over the preceding year, the school ended prayer at public ceremonies, temporarily removed a stop in the interior of Lee Chapel from campus tours for prospective students, and even briefly banned a children’s book on Lee’s horse, Traveller.

From those concerns, The Generals Redoubt was born. The mission of this group of alumni, friends, parents, and students is “the preservation of the history, values, and traditions of Washington and Lee University.” The group’s July 2019 newsletter explains that “A redoubt is a military term designating a temporary defensive position from which offensive operations can be launched. We thought the term aptly described what our group was trying to do.”

In particular, they want to make sure that the men who established and sustained the university are not erased from its history: George Washington, John Robinson, and Robert E. Lee.

The school now bears Washington’s name because he saved what was then Liberty Hall Academy by giving the school its first major endowment in 1796. In 1826, the school was once again struggling. It had only 65 students and little money. That year, trustee John Robinson died and left his estate to the school. Robinson’s generous gift, which included a 400-acre farm, livestock, a whiskey distillery, and 73 slaves, helped save the school from bankruptcy. Robert E. Lee became president of the school, by then called Washington College, in 1865. Lee proved an able and innovative president. Trustees voted to change the school’s name to Washington and Lee University after Lee’s death in 1870. Members of the Generals Redoubt want that history to be acknowledged and preserved, despite its complications.

Tom Rideout, president of the Generals Redoubt, is particularly concerned about the effect of recent changes on Washington and Lee’s students. “Students are disadvantaged in their educational preparation for the world at large,” Rideout said. “And the focus on diversity, inclusion, and identity bloats the staff and payrolls and divides the students.”

Data from the Department of Education corroborate Rideout’s claims of administrative bloat. The number of full-time non-instructional staff per 1,000 Washington and Lee students grew from 241 in 2012-2013 to 291 in 2018-2019. That’s an increase of 21 percent in fewer than 10 years. The largest increase was in “Community, Social Service, Legal, Arts, Design, Entertainment, Sports, and Media Occupations,” which often includes diversity and inclusion personnel. In 2013-2014, there were just 48 employees in those categories. Now there are 113, despite the fact that enrollment has not grown. Washington and Lee spends nearly $9,000 per student on “day-to-day executive operations of the institution, not including student services or academic management” according to the American Council of Trustees and Alumni.

Members of the Generals Redoubt are also concerned about changes in the curriculum, including a proliferation of courses related to identity-driven political agendas focused on race, class, sex, and gender. Neely Young, vice president of the Generals Redoubt, cataloged some of those courses here. A few notable examples are “Queering Colonialism” in the history department and “Post-modernism: Power, Difference, and Disruption” in the philosophy department. “Many of these courses seem to exist to meet the ever-narrowing and increasingly politicized specializations of the professoriate,” Young wrote.

Rideout blames “presentism” for the recent attempts to sanitize Washington and Lee’s history and change its curriculum. The FAQ section of the Generals Redoubt website explains:

During the late ’50s and very early ’60s of the last century, Professor Thomas P. Hughes taught W&L students of the rewriting of Russian history by Lenin and Stalin, both true authoritarians to their core. Today, this dubious academic practice is known as Presentism. Essentially it seeks to apply today’s cultural and moral values [to] the people and events of prior periods. If it finds the two in conflict, the modern view prevails and the well-established history of that era is at risk of significant modification.

The actions recommended by the administration and adopted by the Board of Trustees in the fall of 2018 are clear signs that Presentism is alive and well at Washington and Lee. The Report of the Commission on Institutional History and Community clearly left open the option to remove the names of George Washington and Robert E. Lee from that of the University, which would be the ultimate triumph of Presentism.

Yale dean Anthony Kronman addresses the same issue in his recent book, The Assault on American Excellence, which includes a chapter on memory. In it, he makes the case for living with monuments to the past, even if they do not meet our present standards:

[Dismissing preservationists as] racists in disguise…draws attention away from the special responsibility of our colleges and universities to cultivate the capacity for enduring the moral ambiguities of life. This includes—indeed it is often first aroused by—the need to acknowledge the complexities of a checkered and sometimes discreditable past. The ability to do this is moral strength. It is a species of moral imagination as valuable as it is rare, and as vital to the health of our democracy as to that of our colleges and universities themselves. Its neglect, or suppression, is an educational disgrace.

The zeitgeist at many universities calls for completely erasing the sins of the past from every campus building, quad, and sign, taking with them the university’s place in history. Washington and Lee, with direction from the Generals Redoubt, can show that there is another way. It can set an example of how to live with the ambiguity of the past. Although Washington and Lee is unique, lessons from its experience can inform all of our historic universities as they learn to acknowledge and understand the past.

Jenna A. Robinson is president of the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal.