In 2022, Jon Lauck published The Good Country: A History of the American Midwest, 1800-1900. His book describes a wonderful range of things to love about the 19th-century Midwest: its democratic civic ethos, the enduring Midwestern commitment to antislavery that resulted from the Northwest Ordinance’s original prohibition of the practice, and the wildfire-spread of co-educational colleges in the region. Lauck also adorns his book with wonderful quotations, which illustrate points such as the Midwestern love of literature that made it the talk of every table. “When William Dean Howells was visiting Representative James A. Garfield in Hiram, Ohio, in the late 1860s,” Lauck writes, “Garfield ran around to all his neighbors yelling, ‘Come over here! He’s telling about Holmes and Longfellow and Lowell and Whittier!’” The Good Country provides chapter and verse on why Americans have cause to love the Midwest’s history.

The publication of a book like Lauck’s should not have been news. But it was news, startling news, because the American historical profession has been taken over by a body of professors animated by an extraordinary hostility toward America and Western civilization as a whole.

The story of our wonderful country is being memory-holed by our universities’ history departments.They don’t write books like Lauck’s anymore—not at Harvard, nor at the University of Wisconsin, nor at Denison College. Instead they complete projects with titles like The Children of Lincoln: White Paternalism and the Limits of Black Opportunity in Minnesota, 1860–1876 (2018) and Imagining the Heartland: White Supremacy and the American Midwest (2022). What’s happening to Midwestern history is happening to all of American history. The story of our wonderful country, and the civilizational tradition from which it came, is being memory-holed by our universities’ history departments.

America is desperately short of every kind of professor and public intellectual who knows our Western civilizational heritage and the ideals and institutions that formed and preserved our republic. But we are particularly short of historians. A continuing flow of conservatives into law and the judiciary has preserved a remnant body of tradition-minded law professors to make the case for originalism, natural law, and precedent. Tradition-minded political theorists also survive, as do tradition-minded economists. History departments, by contrast, have become almost entirely a left-wing preserve. History professors’ blatant politicization dissuades most dissenters from applying to history graduate departments, and selective blackballing by admissions committees ensures that the next generation of history professors will be at least as radical as the present one.

Mitchell Langbert’s articles comparing Democratic and Republican voter registration among faculty by academic discipline illustrate the point. His 2016 study found that the ratio of Democrats to Republicans was 4.5:1 in economics, 8.6:1 in law, and 33.5:1 in history. His 2018 study, with a different sample, found that the ratio of Democrats to Republicans was 5.5:1 in economics, 8.2:1 in political science, and 17.4:1 in history. Both studies suggest that tradition-minded historians are far scarcer than tradition-minded scholars in economics, law, and political theory.

The disappearance of tradition-minded historians has affected the character of tradition-minded ideals. Tradition-minded economists and political theorists, shaped by their disciplinary conventions, tend to define proper policy by its adherence to abstract words and principles. Tradition-minded lawyers share far more of the disciplinary presuppositions of historians, but their studies focus relatively narrowly upon the law. Historians, who look more broadly to culture and society, to the individuality of biography, to the contingencies of events, and to the shared experiences of peoples, have receded within tradition-minded scholarship—and within the broader political movements inspired by that scholarship. Tradition-minded scholars, oddly enough, know relatively little of the history that creates tradition.

Americans are forgetting their history because there are no tradition-minded history professors to pass on that story.Yet the disappearance of tradition-minded historians is still more damaging to America as a whole. Americans are forgetting their history because there are no tradition-minded history professors to pass on that story. The radicals who hate American history teach their hatred instead, above all to the nation’s future K-12 social-studies teachers. They pass on this hate-reading of American history to our children.

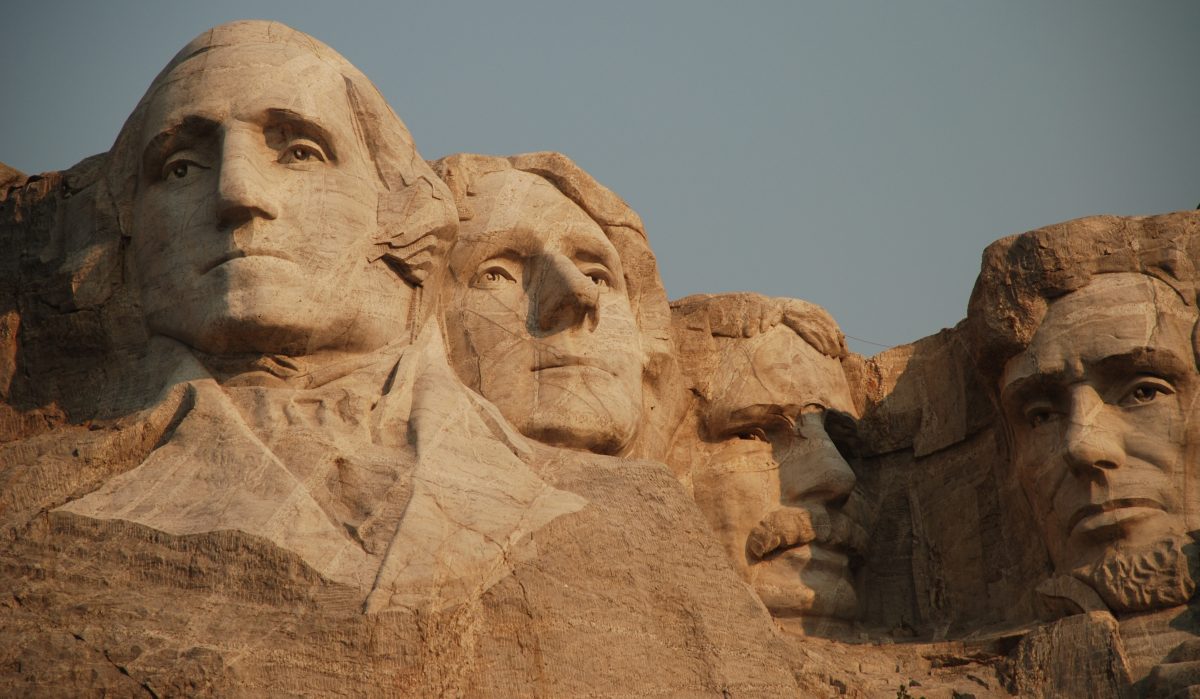

Americans also are forgetting the history of Western civilization—all the history our Founding Fathers knew as they created America, as well as the history that continued to inspire Lincoln and King and Reagan as they strove to preserve and expand American liberty. America needs historians of ancient Greece and Rome, of medieval Christendom, and of the intellectual explosion from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. They need experts in British history, which provides the hinge between Europe and America, and in the Western invention of modern science and technology. They need historians of the law—Roman and canon and common—to preserve our memory of how law and liberty intertwine.

We need new history departments, staffed by historians dedicated to researching and teaching this history of American and Western civilization, to provide competition to the existing radical monopoly. We need, indeed, every sort of history, of every part of the world. Any history we don’t teach well is history we abandon to the radical professoriate desperate to prosecute America and Western civilization more broadly. Such new departments would be popular with the vast number of students who long to learn the real history of America, and it would surely be profitable in the long run. Yet to set up new departments necessarily will require a substantial investment, and we have scarce resources. What should be Americans’ priorities?

We need historians of the American republic—and that means subdisciplines that emphasize the importance of the republic, its survival, its ideals, and its actions. We need, therefore, constitutional historians, who know the constitutional and legal history of the republic and the process by which our ideals entered into and shaped the foundational institution of the republic. We need diplomatic historians, who know how our republic has interacted with its peers and how our ideals and our interests have shaped our foreign policy. We need military historians, who know the victories, defeats, strategies, and sacrifices that shaped the republic’s survival and expansion. We need political historians, who know the narrative of motivations and events that shaped the conflicts and consensuses that generated our constitutional, diplomatic, and military history.

We need historians of the American nation—and that means subdisciplines that emphasize the enduring common character, ideals, and delights of America. We need intellectual historians, who can trace the threads of thought that unite Americans, such as the City on a Hill invoked by John Winthrop and Ronald Reagan. We need religious historians, who can delineate Americans’ faiths and explain how they have influenced American beliefs and actions. We need cultural historians, who can describe the common culture that delighted Americans and the world. We need social historians, who can describe how the mores of liberty and equality struck deep roots in American society. We need economic historians, who can describe how entrepreneurship and industry made America the wealthiest nation on earth. We need science and technology historians, who can describe how a nation of tinkerers became a nation of mass production, computers, and space travel.

We need historians to preserve the chain of predecessors to whom America owes its ideals.We also need historians to survey Western civilization: the ancient world, medieval Christendom, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, British history, legal history, and the history of science and technology. But we need above all historians to preserve the memory of the chain of predecessors to whom America owes its ideals and institutions of liberty: Pericles’ Athens and Cicero’s Rome, Salutati’s Florence and the Great Britain of the Glorious Revolution. America needs at least a sketch of how liberty was handed down from one generation to the next throughout the history of the West.

America needs these three clusters of historians: of the American republic, of the American nation, and of Western liberty.

The new Centers that have begun to appear in America’s public universities, in Arizona, Florida, North Carolina, Ohio, Tennessee, and Texas, would be a natural home for such clusters of historians to compete with the radical, illiberal establishment of the history departments. Tradition-minded philanthropists might also seek to endow such clusters of historians in private colleges and universities. Whether in private or public universities, support for tradition-minded historians is even more urgent than support for tradition-minded political theorists, lawyers, and economists. All tradition-minded scholarship is endangered, but tradition-minded history is near extinction.

Theodore Roosevelt wrote that “a nation’s greatness lies in its possibility of achievement in the present, and nothing helps it more than the consciousness of achievement in the past.” We must have historians who know the greatness of America’s past if we would have America be great again.

David Randall is the research director of the National Association of Scholars.