In 1986, Lehigh University freshman Jeanne Clery was raped and murdered in her on-campus dormitory. This terrible event led to the passage of the Clery Act (1990), which requires American universities to publish an Annual Security and Fire Safety Report each October. The purpose of these reports is to provide the public with campus crime statistics in an effort to improve student safety. Yet, despite lawmakers’ noble intentions, Clery Act reporting remains confusing and seemingly arbitrary. Furthermore, it implies that campuses are especially dangerous, while in fact the opposite is true.

Like their peer institutions across the nation, the 16 universities in the UNC System published their 2022 Clery reports by October 1 of this year. Each new report provides at least three years of data (2019-2021) across 21 criminal categories. For the purposes of this article, the authors looked at six of those categories at three representative UNC-System schools: UNC-Chapel Hill (the flagship), UNC Charlotte (an urban institution), and Western Carolina University (a rural one). We also examined previous years’ Clery reports, which allowed us to look for data trends beginning in 2016, well before the dawning of the #MeToo movement and any attendant surges in campus sex-crime reporting.

Data “exceptions” reveal the inherent arbitrariness of the Clery Act system.Full disclosure: The authors approached these data expecting to see #MeToo-related spikes in sex-crime accusations in 2017 and 2018, at the height of the “Believe All Victims” frenzy. Yet the numbers don’t bear out that narrative. With exceptions so specific that the institutions themselves felt the need to comment on them (see below), not only rapes but fondlings, dating violence, and stalking incidents saw no dramatic jump between 2016 and 2018. Nor did the number of reports fade in 2019-21 as #MeToo waned as a political force.

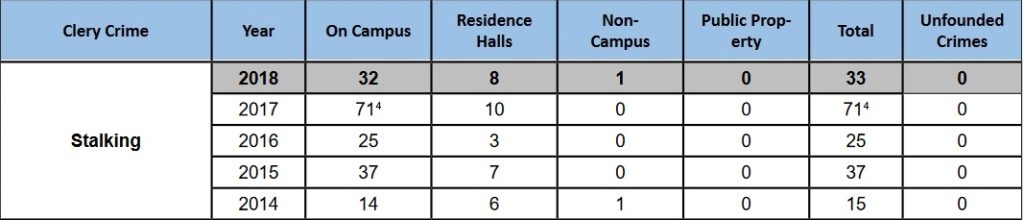

Nevertheless, the aforementioned exceptions are worth noting, if only because they reveal the inherent arbitrariness of the Clery Act system. As the following excerpt from UNC-Chapel Hill’s 2019 report reveals, the number of stalking incidents experienced by Chapel Hill students nearly tripled between 2016 and 2017.

However, an explanatory note makes clear that “31 individuals on campus reported receiving multiple distressing emails from [a single] off-campus individual, [which meets] the definition of Clery stalking.”

As the university obviously recognizes, 31 instances of stalking committed by a sole offender are, while horrifying, entirely different than 31 unconnected crimes. Yet the Clery Act requires that they be treated equally, which means that the public would have an extremely flawed understanding of stalking rates at Chapel Hill were it not for the institution’s easily missed footnote.

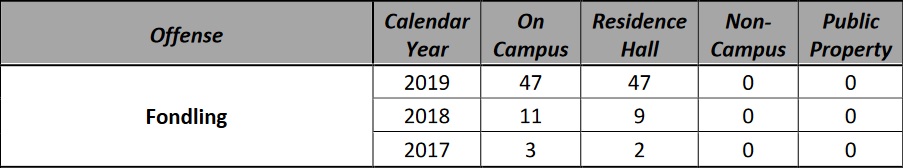

Similar confusion can be found elsewhere. Looking at the “fondling” statistics on Western Carolina University’s 2020 report, one finds a 2019 rate that is wildly disproportionate to that of previous years.

Here, too, a footnote tells the tale. As the 2021 report would go on to acknowledge, the 2019 figures are misleading. “Two separate cases involved instances of 20 counts of fondling over a period of time.”

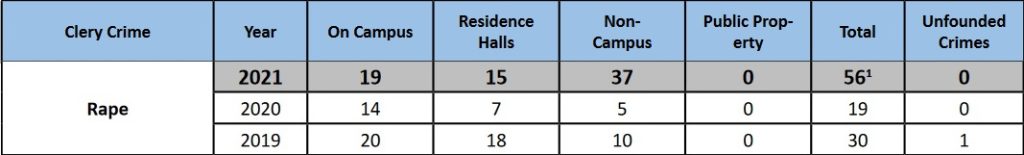

Or consider Chapel Hill’s rape statistics, as rendered in its 2022 report.

Looking at the raw numbers alone, one might easily conclude that UNC-Chapel Hill experienced a plague of sexual assault in 2021, with particular harm done at its “non-campus” (i.e., off-campus but university-controlled) locations. The truth, told once again in a footnote, is that 20 of the non-campus incidents occurred “over the course of [a single] abusive relationship.” Despicable, yes. But not exactly what the data would seem to indicate to the casual observer.

Further muddying the water is the widely tolerated practice of altering a particular year’s data in subsequent reports.Further muddying the water is the widely tolerated practice of altering a particular year’s data in subsequent reports. For example, 2017’s numbers can be viewed in the 2018, 2019, and 2020 reports at the very least. (Institutions sometimes include more than three years in a single document.) Hypothetically, those data should remain constant across every report that lists them. Yet UNC-Chapel Hill’s 2017 stalking number (71, according to the 2018, 2019, and 2020 reports) is listed as a mere 31 in the 2021 report. What happened?

According to the university’s media relations manager, “UNC-Chapel Hill conducted a full file review in partnership with consultants from Margolis Healy and determined that [the incidents involving a single off-campus individual] did not meet the definition of stalking.” As the reader will surely agree, this is a perfectly reasonable explanation. But here, too, we see the futility of the Clery project. For three years, Chapel Hill owned up to a stalking rate that was more than twice as bad as what the university now acknowledges. Did the reality on the ground change when the calendar flipped to 2021? Of course not. One arbitrary system of counting merely gave way to another.

Though understandable, confusion of this sort is nevertheless harmful. This is the case because crime on campus is an inherently political matter, never more so than in our present age of outlandish ideological distortions. Take, for example, the widely repeated canard that one in five women are sexually assaulted in college. Though entirely debunked, the claim was on every lip in the middle of the last decade and seemed at times like the foundational “fact” underlying the Obama administration’s higher-ed policy. The truth is, of course, that colleges are safer than their surrounding communities, and it isn’t particularly close. To the extent that Clery reports disguise or ignore that information, they do an actual disservice to the public they are designed to serve.

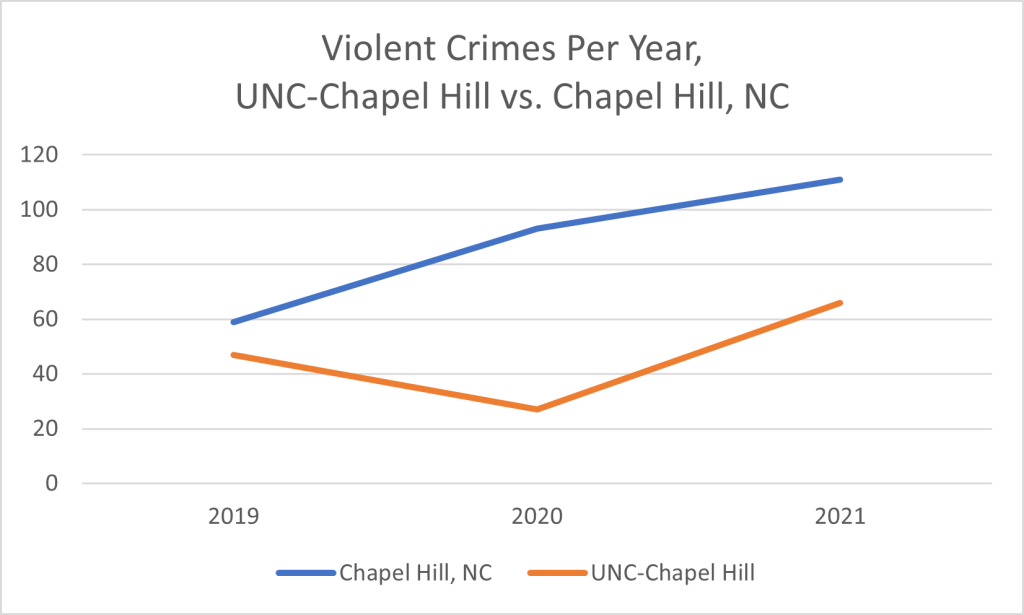

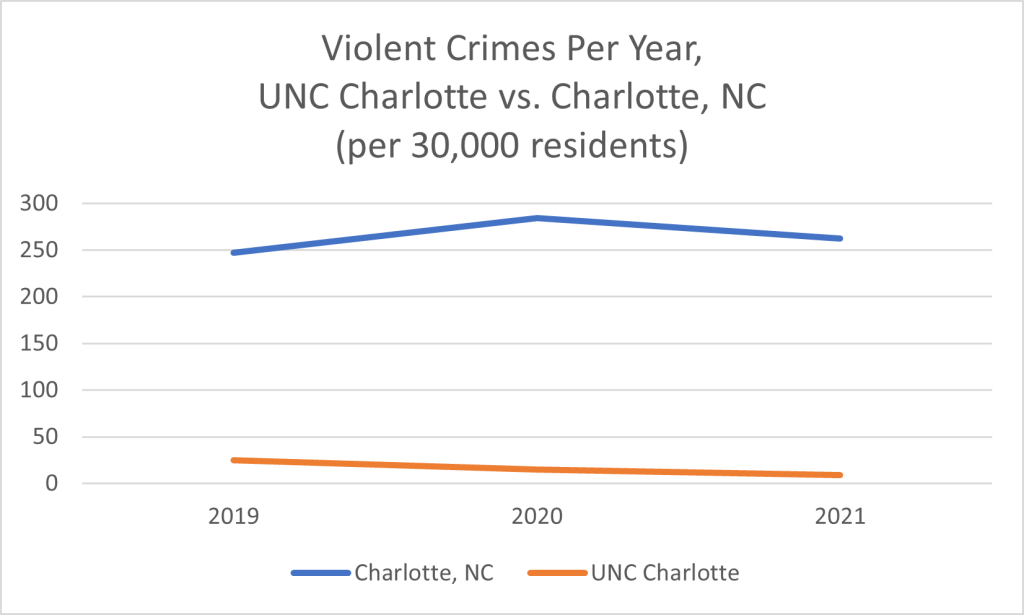

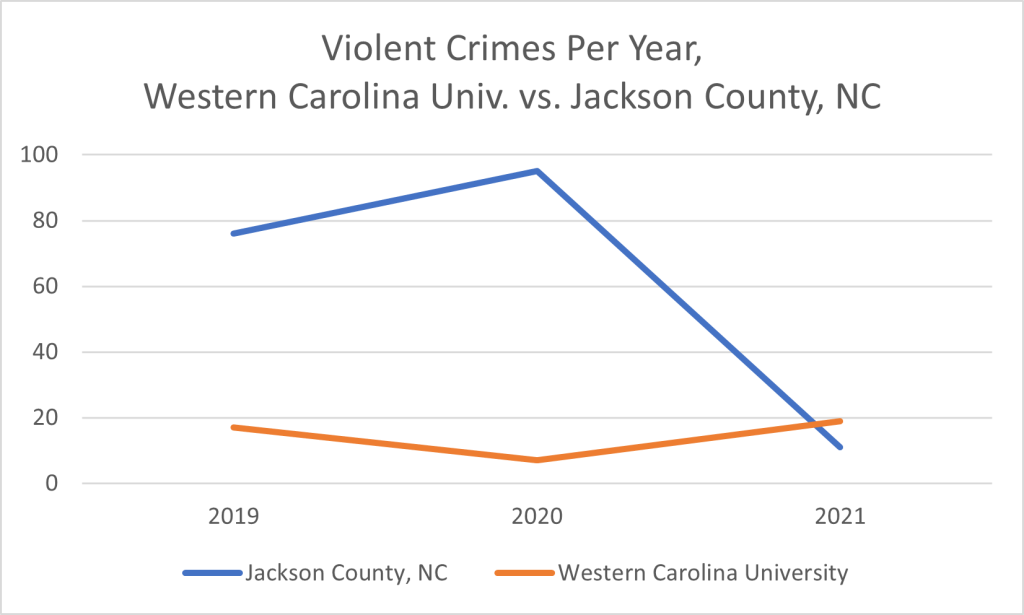

Below, we chart the number of violent crimes (homicide, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault) over the last three years at each of the three UNC-System institutions under consideration. We include also the number of violent crimes in the surrounding communities, using figures from the FBI’s National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS).

This method of tabulation is obviously imperfect. For one thing, communities and campuses have differing and overlapping populations. (In the case of our UNC Charlotte vs. Charlotte, NC, comparison, we have attempted to correct for the population disparity.) For another, the FBI’s crime numbers are self-reported by individual police and sheriff’s departments with little oversight. (Did Jackson County really have only 11 violent crimes in all of 2021?) Still, a clear picture emerges. On the whole, college campuses experience less crime—often far less crime—than the surrounding locales. That this is true at the flagship university, on an urban campus, and on a rural one merely illustrates the point.

Are Clery reports designed to mislead? Of course not. Yet their very existence serves a political narrative that needs pushing back against if not outright dismissal. Colleges are not dangerous but safe. We should all celebrate that fact, not run from it.

Graham Hillard is the managing editor of the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal. Natalia Mayorga recently graduated with a bachelor’s in psychology from UNC-Chapel Hill and is a Martin Center intern.