In late 2023, a new book on law and legal education is coming out (Legally Blind). In the book, I explain how ideology is affecting legal theory, teaching, and the larger law industry, including its entrenched ways of doing business. This all starts with the law schools, and fixing the problem will involve reconsidering how such institutions are categorized and ranked.

At present, law-school rankings function mostly as sales and branding mechanisms rather than providing an actual managerial report that reflects institutional performance. They speak very little, if at all, to the way a school is run operationally and its specific strategic plans.

Law-school rankings flatter a handful of schools, while the rest languish year after year for no apparent reason.Moreover, law-school rankings are backward looking: The reviewers and organizers of the surveys are mostly media staff, and their objective is to market and sell the rankings report, as well as to generate advertising spending, newsstand sales, subscriptions, cross-selling, and “hits” for digital data purposes. They flatter a handful of schools, while the rest languish year after year for no apparent reason.

The magazines and media companies that run the annual rankings are not able or qualified to tell you very much about the content of each of the law-school programs they examine. (There isn’t much they can tell you about standard law courses, which merely conform to Bar requirements.) Instead, the rankings honor university endowments, investment and donor activity, and the depth and magnitude of corporate and governmental cross-interests. (Harvard, Texas, and Yale are effective hedge funds, with over $30 billion each in investable assets.)

In an interesting coincidence, the Yale Law School, generally ranked for decades as “#1,” recently decided to pull out of the U.S. News & World Report law-school ranking program. (It actually can’t “withdraw,” but that’s another matter.) Suddenly, the entire rankings status quo seems suspect. Perhaps it is. But there’s more: Certain law schools like Yale are presently motivated to “re-position” themselves as more populist, less elitist, more accommodating, and less critical. But they also know that the law-school rankings game may be up, and, in order to survive a larger political wave that rejects American classical libertarianism and embraces progressive socialism, their new “particolored garb” is a transformation into “The People’s Law School.”

Yale Law (and Harvard, Berkeley, and the other schools that have now “withdrawn”) may be expressing a concern beyond their assertions that rankings disadvantage students with fewer financial resources, or that they discourage public-service career ambitions. These law schools may well be exiting the retail rankings in order to bring about media compliance with their new branding criteria, which revolve around various interpretations of equity (as this recent Wall Street Journal report describes). This is, of course, a proxy for affirmative action. But it is also a bit of a red herring, as Yale and Harvard have dominated the retail rankings for decades and are under some pressure to avoid being seen as a monopoly in many parts of the legal system, including at the U.S. Supreme Court.

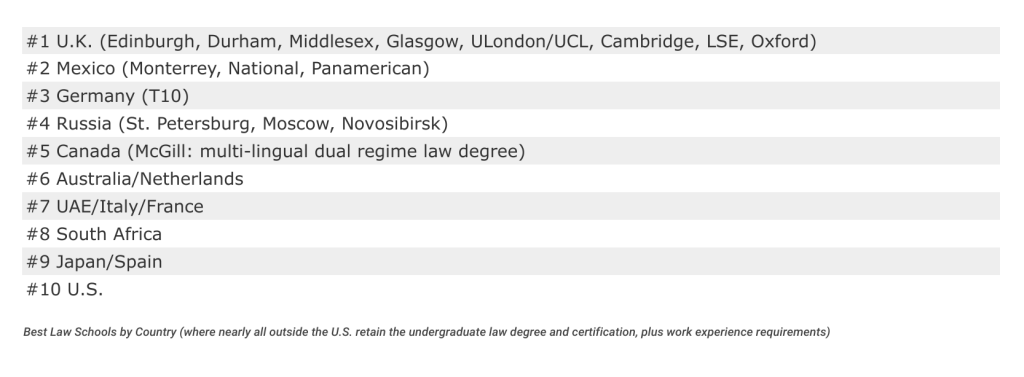

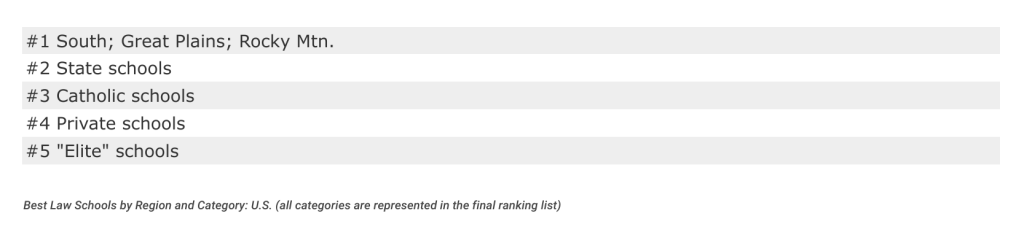

This brings us to our new rankings system. The novel ranking model that follows consists of a three-part “global” filter rather than a mere list of schools. It begins with geography—specifically, with the host country, which places the U.S. in a larger context of international higher education. It then returns to the U.S. market and segments it by regional location, from which much can be discerned about institutional culture and priorities.

Few if any of the traditionally elite law schools have made non-cosmetic changes in literally a century.In this essay I discuss only the “tails” of the ranking distribution—the best and the worst—as, like most things, law schools follow a fairly normal distribution. The vast majority make up the area a mere one or two deviations from the mean. Furthermore, unlike the traditional mass-media rankings, I rank only 50 law schools, with an emphasis not on dominance but on change, experimentation, and focus. Few if any of the traditionally elite law schools have made non-cosmetic changes in literally a century. Some courses change names, and professors come and go, but, outside of tuition escalation, such schools are defined by their rigidity of content, their consensus in jurisprudence, and their consolidation of methods.

The reality is that the U.S. has the worst law schools if measured on a global efficiency basis. U.S. legal training requires seven years (B.A. plus J.D.), while the U.K. requires a total of three (the LL.B.). We have some fine law schools but spend entirely too much training the next generation of attorneys.

Given these facts, my new proposed rankings system looks for several indicators of structural improvement and program improvement, in the spirit of “lean” management that lowers waste and cost. A few law schools are taking steps in those directions, and they deserve more consideration.

So, first, country rank:

Second, the U.S. regional and category rank.

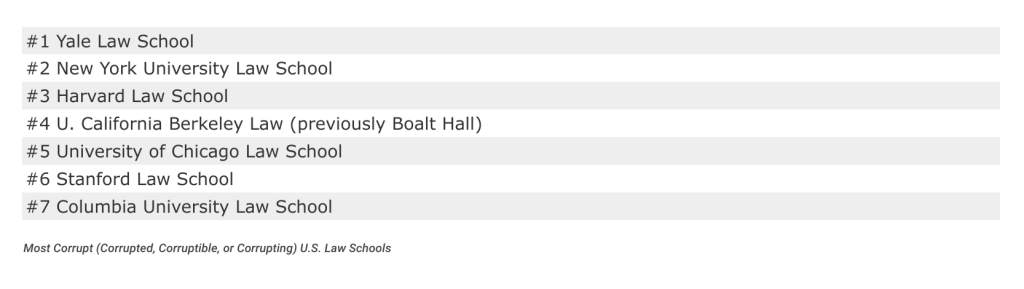

Third, rank by corruption, following a corruption index. This category is populated exclusively by so-called elite law schools.

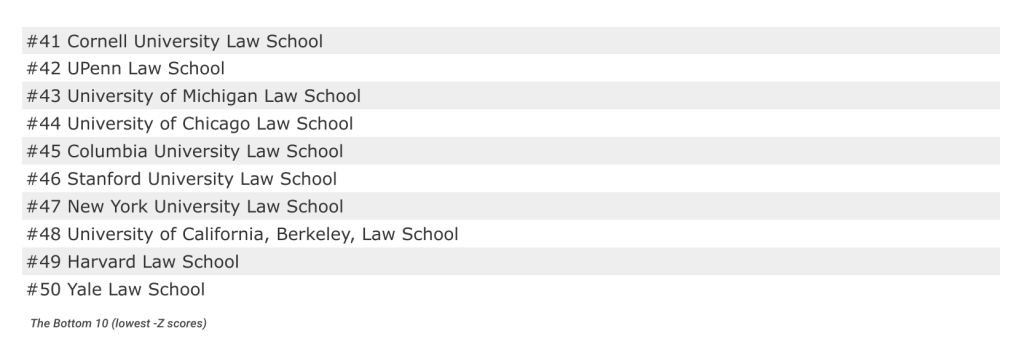

The result is a bottom 10 …

and a top 20 …

By now, you may be wondering how I picked these schools and what filters were used. Indeed, you may be saying that this is just a “red-state, conservative, Catholic re-mix.”

Well, no, not at all—despite the fact that traditional rankings contain an explicit “conservative penalty and liberal bonus.” (I would invite you to explore each of these schools yourself, but a few words may be helpful, and more is discussed in detail in the book.)

Traditional rankings contain an explicit conservative penalty and liberal bonus.I do not view “rank” as a consolidation or solidification achievement, but rather as a temporal recognition of current managerial capability, economics, trade preparation, teaching focus, and culture. Proximity to intra-university STEM and social sciences also plays a part. Some of the schools here have been selected on the strength of the dean (one person makes a difference); others because of a broader institutional functionality; still others because of a values perspective, where “values” are defined in ways that reinforce the rule of law and ideological neutrality.

I make no apologies for recognizing several Catholic law schools but recognize non-denominational ones equally. Still others have been selected based on their applications of law—for example in natural resources, air and space, or media and entertainment.

Lastly, there are some law schools that have been recognized for their ability to resist what Robert Bork described as “the political seduction of law.” Such schools tend to have independent-minded leadership.

How were the “Bottom 10” determined? In some ways, they are the “anti-Top 20” in their institutional failure to resist political temptation, especially at a federal level. But there are other key factors that make them problematic places to study law, as well. These include:

- corruption, cost, content, and culture (the “4Cs”);

- economic inefficiency;

- especially skewed student- and faculty-population profiles;

- resistance to structural modification (for example, reducing time-to-degree);

- political co-option and partisan institutionalization;

- weak administration and susceptibility to special-interest influence;

- disregard of foreign conflicts of interest;

- difficulty in establishing neutral or objective legal information;

- irregular feedback, training, testing, and evaluation of academic faculty;

Traditional rankings present a fundamental philosophical problem, in that they support the pretenses that law is something separate from you and your life (it isn’t); that law professors know more about natural law than you do (they don’t); and that the practice of law is a hierarchical intellectual and reasoning act (only partly). Breaking down the traditional rankings myth is among the steps necessary to breaking down the legal barriers that protect pricing distortions, limit technical advancement, and reinforce intellectual corruption and economic waste. It can’t happen soon enough.

Matthew G. Andersson is a technology professional, a former CEO, and the author of the forthcoming book Legally Blind: How Ideology Has Captured the Law School, the Judiciary and the Constitution.